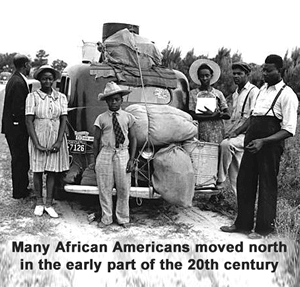

When the United States entered World War I, most African Americans lived on farms in the southern part of the country. They were technically “freed” after the Civil War, but most black Americans lived in extreme poverty. Better-paying jobs in factories and railroads in the North, but European immigrants usually filled those jobs.

The flood of immigrants stopped when war broke out. The factory jobs they usually filled were now open to African American workers. By 1920, more than 350,000 African Americans had moved from their homes in the rural southern states to northern cities. They settled in railroad and industrial centers such as New York, Boston, Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, and Cleveland.

Move_North

White farmers and business owners in the South depended on African American workers to fill low-paying jobs. Communities in Georgia and Mississippi passed laws limiting the number of African Americans who could ride trains. The mayor of New Orleans formally requested the Illinois Central Railroad president to stop all northbound trains carrying African American passengers.

White farmers and business owners in the South depended on African American workers to fill low-paying jobs. Communities in Georgia and Mississippi passed laws limiting the number of African Americans who could ride trains. The mayor of New Orleans formally requested the Illinois Central Railroad president to stop all northbound trains carrying African American passengers.

The African Americans found jobs in the North, but they also found resentment and prejudice. Almost all unions were closed to African Americans. In some cases, the resentment erupted into violence.

African American men did serve in the American army, but most were only allowed to work in menial jobs. They worked as kitchen staff or dockworkers. Three all-black divisions fought at the front, but white officers commanded those divisions. The American army did not integrate until after the Second World War.

Resources

Download this lesson as Microsoft Word file or as an Adobe Acrobat file.

Mr. Donn has an excellent website that includes

a section on World War I and World War II.

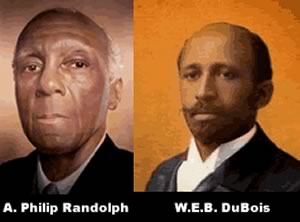

Two Perspectives

Many African American leaders opposed participation in the Great War. A. Philip Randolph argued that African Americans should not participate because they were denied “full citizenship.” W.E.B. DuBois disagreed, arguing, “while the war lasts [we should] forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens and allied nations that are fighting for democracy.”