Charlemagne ruled the most significant Western European Empire after the fall of the Romans. Four forty-three years until he died in 814, Charlemagne amassed an empire that extended more than 800 miles from east to west. Though he ruled in an era many scholars describe as a “Dark Age,” Charlemagne made the capital of his vast kingdom a center of learning.

Charlemagne was a Frank, a Germanic-speaking people who dominated present-day northern France, Belgium, and western Germany. He was part of the Carolingian Dynasty begun by his father, Pepin the Short, and named for his grandfather, Charles Martel. A giant of a man, Charlemagne was six feet, four inches tall in an era when most men were little more than five feet tall.

Charlemagne inherited his predecessors’ talent for war, leading his army on military campaigns throughout Western Europe, expanding his kingdom as he vanquished his foes. During his reign, Charlemagne doubled the size of Frankish territory to include present-day France, northern Spain, Germany, and Italy.

Charlemagne

Charlemagne (c. 747 – 814), also known as Charles the Great, was the King of the Franks from 768, and from 800 the first emperor in western Europe since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. ”

Charlemagne sought to unite all Germanic tribes into a single kingdom modeled after the Romans. The Frankish kingdom eventually included people of diverse cultures who spoke many languages, so Charlemagne appointed native members of his conquered lands to administer the provinces in his name.

Charlemagne provided funds that allowed monks to copy the works of Greek and Roman authors. Couriers traveled throughout Europe to collect ancient manuscripts. Although Charlemagne could barely read, he set up schools throughout his empire and invited European scholars to establish a palace school in Aachen, the German city where he moved his capital.

Holy_Roman_Empire

In 800, Charlemagne traveled to Rome to celebrate Christmas with Pope Leo III. As Charlemagne rose from prayer, Leo placed a crown on Charlemagne’s head and proclaimed him Augustus, emperor of the “Holy Roman Empire. The coronation united Christendom under Charlemagne’s rule but also troubled the newly crowned emperor. If the Pope had the power to proclaim Charlemagne as King, the Pope might also have the right to remove his power.

Charlemagne did not invite the Pope when he passed the crown to his son in 813. Nealy a millennium later, as Pope Pius VII was set to crown Napoleon Emperor of France in 1804, Napoleon took the crown and placed it on his head.

Christmas Day 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1804, Napoleon was about to be crowned Emperor of the French. At the moment of his crowning, Napoleon unexpectedly took the crown from Pope Pius VII and crowned himself.

The empire Charlemagne created crumbled soon after he died in 1814, and the promise of returning the glory of Rome to Western Europe soon faded. The term Holy Roman Empire described various Frankish and German lands for another ten centuries, but the empire never again attained Charlemagne’s promise. Francis II was the last monarch to call himself the Holy Roman Emperor. But after a defeat by Napoleon’s army, Francis renounced his title in 1804 and instead decreed himself emperor of Austria.

Resources

Download this lesson as Microsoft Word file or as an Adobe Acrobat file.

Listen as Mr. Dowling reads this lesson.

Mr. Donn has an excellent website that includes a section on the Middle Ages.

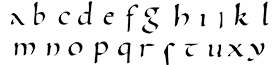

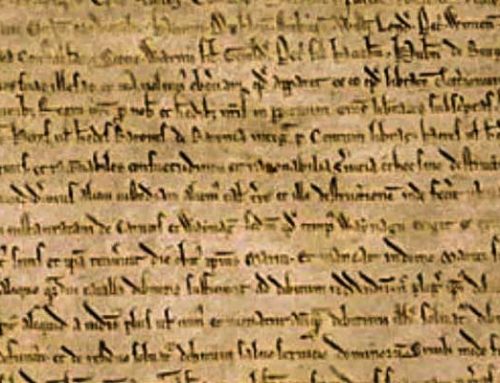

Charlemagne’s Script

Before the invention of the printing press, books were written by hand. Early manuscripts had no standards. There was little punctuation, and scribes often made their letters quite different. Copying entire manuscripts was difficult and time-consuming, and the animal hides used before modern paper was expensive. Scribes often used abbreviations and allowed words to run together to speed up the process and save space.

Charlemagne wanted to make reading more accessible, so he encouraged a calligraphic standard called Carolingian minuscule to be used throughout his kingdom. Scribes trained in Carolingian minuscule made distinguishable letters, placed spaces between words, and used standardized punctuation. They wrote titles in capital letters to make scanning the manuscript more accessible for a reader. Today, over 7000 manuscripts written to Charlemagne’s standard are available for modern scholars to study.